The TRIADS Framework describes evidence-informed practices for screening, provider response, and patient education about Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) in primary healthcare settings.

Jump to section:

Defining TRIADS

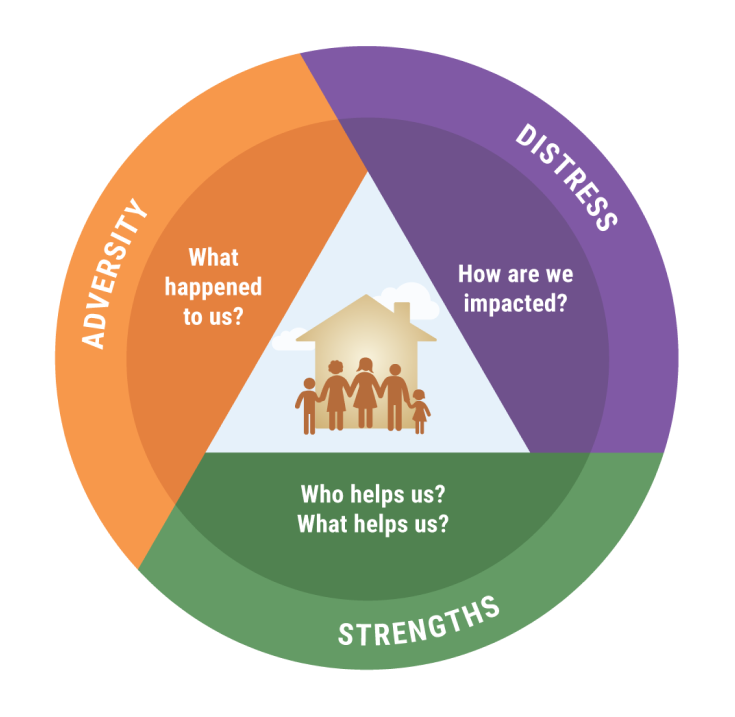

The TRIADS Framework (Trauma and Resilience-informed Inquiry for Adversity, Distress, and Strengths) describes an evidence-informed approach for screening, provider response, and patient education about Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACES) in healthcare settings.

The development of TRIADS was informed by community wisdom derived from interviews with patients and other community members, evidence-based interventions for traumatized children and families, and influential trauma and resilience-informed clinical change frameworks for both pediatric and adult medicine1-5 TRIADS is also aligned with Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA) practices and principles of trauma and resilience-informed care6, and the “ACEs and Toxic Stress Risk Assessment Algorithm” developed by the ACEs Aware initiative.

The TRIADS Vision

Trusting relationships are at the core of all healing endeavors. Relational health is the underlying vision of the TRIADS Framework. We understand relational health as physical, emotional, and behavioral wellbeing that is promoted by healthy relationships. We aspire to build, support, and strengthen relationships between patients, their families, their communities and their healthcare team based on values of equity, respect, and inclusion of diverse cultural and community values. Our vision includes engaging the whole family in a relational model of healing because healthy parents, caregivers, and other family members are crucial to promote healthy development in children and adolescents.

The TRIADS Framework understands adversity as a universal human experience that occurs in the context of embedded ecological risk factors, including painful family circumstances; racism, xenophobia, and discriminatory systemic practices; structural power inequities for low-income and minority racial, ethnic, and cultural groups; and intergenerational patterns of historical group trauma that continue into the present.

Patients with histories of adversity often experience healthcare and other systems as impersonal, judgmental, and harmful. For this reason, we believe that it is essential to conduct ACEs screening and response within a safe and caring healthcare team-patient relationship. We envision a purposeful expansion from a biomedical focus on disease and dysfunction to a bio-psycho-social-spiritual focus on strengths and healing. This expansion starts with the healthcare team’s authentic and non-judgmental interest in patients’ life experiences. The journey to more holistic healing includes learning about patients’ experiences of maltreatment, discrimination, and racism as well as their sources of resilience, defined as the individual’s use of personal and community strengths as protective factors to mitigate and recover from the harmful impacts of adversity.

The expansion from a biomedical paradigm to a bio-psycho-social-spiritual model of human development and healing calls for a holistic understanding of individual patients in three related areas: 1) adverse life circumstances from personal experiences and structural inequities; 2) signs of physical and psychological distress and 3) patients’ strengths and self-care practices that affect health outcomes. Clinical attention to this triad allows for a more “actionable” understanding of individual patients than any one area alone. To truly transform the quality of healthcare, the medical system and individual providers must understand and respond to patients’ adversity and distress while enlisting their strengths in creating and implementing the treatment plan.

TRIADS employs three core intervention strategies, listed below.

- ACEs Screening: Asking with empathic interest about the patient’s experiences of adversity and trauma.

- Assessing Distress: Describing in a supportive, non-judgmental manner the possible links between the patient’s adverse life experiences and presenting physical and emotional health conditions associated with ACES, including behaviors and habits that may be harmful to health.

- Identifying Strengths: Guiding the patient to identify personal characteristics, relationships, or community resources that provide support and enhance wellbeing.

The TRIADS Framework uses these strategies to practice a holistic approach to healthcare that helps patients understand how ACEs may affect their physical and emotional health, promotes their motivation for self-care by identifying helpful personal and environmental resources, and engages patients as active partners in creating their treatment plan. The sections below provide definitions of Adversity, Distress, and Strengths.

Watch & Learn

Putting Relational Healing Into Practice

Dr. Alicia Lieberman, Professor of Psychiatry at UCSF and Director of the Child Trauma Research Program, shares how clinicians can put the concepts of relational healing into practice.

Using TRIADS With Patients

Sara Johnson, M.D., a practicing OB-GYN in Oakland, shares how she incorporates TRIADS into her clinical practice.

Becoming a More Effective Physician

Eddy Machtinger, M.D., Professor of Medicine at UCSF, describes how he thinks TRIADS has made him a more effective physician.

Adversity

Asking with empathic interest about the patient’s experiences of adversity and trauma

Adversities are difficult life events that elicit heightened physiological and psychological stress responses. The term became widely used with the dissemination of the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study (ACEs)7,8 , which reported that 10 types of childhood adversity were strongly correlated in a stepwise fashion with heightened risk for many of the most common and serious adult medical and psychiatric illnesses. The original ACEs include physical, sexual, and emotional abuse; witnessing violence against the mother; a primary caregiver with mental illness or substance misuse; a primary caregiver in prison; growing up with a single parent; physical or emotional neglect; and loss of a parent by death, separation, divorce, or other reasons. Some of these adversities qualify as traumatic events using the definition of the American Psychiatric Association12 because they involve exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence either directly or by witnessing it as it occurred to others. Since the original study, social conditions such as racism, discrimination, traumatic migration, food insufficiency, and poverty have been identified as additional adversities that are linked with many of the same adult medical and psychological conditions9,10.

Distress

Asking supportively about physical and emotional health conditions associated with ACES, including behaviors and habits that may be harmful to health

TRIADS uses the term Distress to describe the diverse manifestations of physical and emotional dysregulation and dysfunction that may be observable in clinical practice. Expressions of distress include many of the most common illnesses and physical and behavioral symptoms seen in pediatric and adult primary care. Assessing for symptoms of distress at the somatic, emotional, and behavioral levels and establishing the existence or risk for ACEs-Associated Health Conditions by healthcare teams is an important addition to the health care visit. Please refer to the comprehensive list of ACE-Associated Health Conditions (AAHC) in children and adults11.

Distress encompasses a range of manifestations, from physiological imbalance, somatic symptoms, and psychological discomfort to medical conditions associated with cumulative adversity (also known as ACES-Associated Health Conditions)11. The common denominator across different forms of distress is that the magnitude of the adversity overpowers the patient’s coping mechanisms and ability to maintain healthy functioning and wellbeing. Different manifestations of distress can co-occur, reinforce each other, and escalate the overall scope of distress and the risk for associated health conditions. For example, depression may be expressed through chemical imbalances, loss of appetite or overeating, sleeping problems, and lack of energy, which in turn may trigger or exacerbate medical conditions.

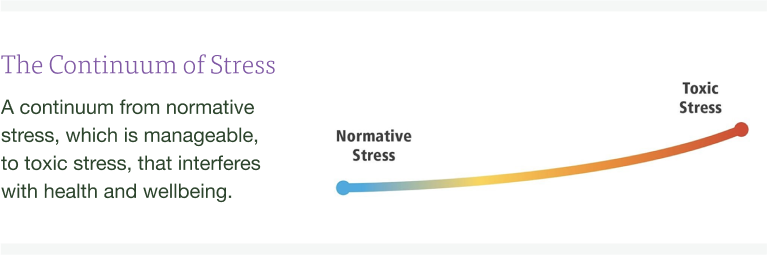

The figure below illustrates a continuum from normative stress — which is expectable and manageable — to toxic stress that interferes with health and wellbeing.

- Normative stress is a manageable heightened physiological and psychological response to a challenge that is followed by return to homeostasis and physiological balance. Normative stress provides energy and motivation to achieve immediate and long-term goals. For example, children are usually stressed when they first start school but they grow and learn from this challenge. Adults may respond with stress to deadlines but this heightened arousal impels them to complete the task. Normative stress enables individuals to change their behavior and adapt effectively to new situations.

- Toxic Stress is defined as a chronic physiological arousal in response to frequent, intense, or persistent threats without returning to physiological balance. It involves the continued release of high levels of stress hormones that create chronic physiological imbalance and undermine the individual’s stress management system, including the ability to deploy adaptive coping strategies and to make use of protective relationships and resources. Toxic stress can be caused by individual and family-level stressors as well as by threatening social conditions including systemic inequities, poverty, violence, discrimination, racism, and xenophobia. Toxic stress has varying degrees of intensity, ranging from chronic stress in response to persistent adversity to traumatic stress in response to specific life-threatening events. It is important to recognize the distinction between traumatic stress, which can have a range of impacts and manifestations, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which is an algorithm- based psychiatric diagnosis that may result from exposure to specific forms of trauma such as actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence12.

Individuals are often unaware of the causal connections between exposure to adversity and manifestations of distress. Understanding that symptoms of distress may be traced back to adverse life experiences can help the healthcare team explain to the patient the possible origins of their health conditions and help design effective treatments. For example, a patient’s depression and substance use are likely to be treated more effectively if the healthcare team or mental health consultant also understands the origins of these conditions in the patient’s traumatic experiences and adopts a supportive approach to working with the patient to develop a treatment plan.

Identifying distress

Distress may be expressed in physical symptoms, behavior, and/or emotions. Distress may be manageable or cause significant difficulties depending on its duration and intensity, factors which are in turn influenced by underlying constitutional, situational, and cultural factors.

- Physical manifestations. Examples include AAHC in the forms of endocrine, metabolic, immune, inflammatory, and cardiovascular problems, disturbances in eating (loss of appetite or overeating), sleeping (insomnia, oversleeping, night waking, nightmares), digestion (constipation, diarrhea), frequent illness or pain (unexplained weight loss, headaches, or stomach aches with no known medical cause), lack of energy, and multiple childhood and adult health conditions such as asthma, obesity, and diabetes11.

- Behaviors. Examples include relationship conflicts, risk taking, angry outbursts, aggression, self-harming behaviors, and substance use.

- Emotional difficulties. Examples include intense and persistent sadness, anxiety, depression, irritability, anger, and loss of pleasure in relationships and activities.

Strengths

The role of the healthcare team as a protective factor

Strengths are individual, family and community characteristics that protect against the impact of adversity and promote resilience and recovery. There are three basic reasons to include strengths as a key focus of inquiry.

- Acknowledging strengths promotes hope. Healthcare team providers create a more positive relationship with their patients when they highlight the patient’s strengths in addition to addressing adversity and distress.

- Understanding how patients use their strengths to manage and alleviate the impact of adversity and distress can enable the healthcare team providers to tailor the treatment plan to the specific circumstances of the patient and the family.

- Learning about a patient’s strengths allows the healthcare team to elevate the importance of individual, family, and community protective resources as integral parts of the treatment plan.

Protective factors involve personal characteristics, supportive relationships, and community resources. There are, in addition, societal protective factors that are basic to health and wellbeing, such as food sufficiency, adequate housing, safe neighborhoods, well-functioning schools, employment opportunities, and timely access to healthcare. The list below includes examples of individual, family, and community protective factors that offer support in coping with life challenges.

- Individual characteristics associated with resilience, which is defined as the capacity to adapt successfully in the context of significant exposure to adversity. These characteristics include good cognitive skills; appealing personality; self-efficacy; optimism; motivation to succeed; and religious faith or spirituality (13).

- Supportive interpersonal relationships (friends and family) are the most reliable predictors of health and wellbeing across the lifetime. Research also shows that having at least one caring adult during childhood can help prevent or reverse the negative health impacts of adversity.

- Supportive community settings like faith institutions, social clubs, or volunteer organizations offer a sense of belonging and higher meaning.

- Self-care activities that can promote personal growth and relaxation. These include spiritual pursuits, reading, learning, meaningful connection with others, and time in nature.

- Pleasurable activities, which include intellectual interests, sports, and hobbies that maintain physical and mental engagement in learning.

The role of the healthcare team as a protective factor.

Patients are often hesitant to reveal adversities and distress even when these conditions stem from events beyond their control. This reluctance can be due to the sense of shame that often accompanies adverse events, a history of judgmental or dismissive experiences in healthcare settings, or an impression that healthcare settings are not the place to address personal adversity. Healthcare teams can create a supportive context for the screening when they make an introductory statement explaining that adverse events and resulting distress are very common and can affect health, and that people are not to blame for their difficult life circumstances.

The healthcare team can then build on this supportive introduction, explaining that treatment can be more effective when the healthcare team and the patient share an understanding of the patient’s difficult experiences, state of mind, and sources of strength and comfort. Studies show that patients find relief from disclosing painful experiences to someone they trust when these disclosures are met with an empathic response. Patients also respond positively when the healthcare team follows up questions about adversity and distress by asking with genuine interest about their sources of strength, using questions such as:

“What helps you the most when you are feeling down?”

“What makes you feel good?”

“What do you like to do?”

These questions can encourage patients to acknowledge and cultivate areas of goodness in their lives.

Conducting the screening in ways that support the patient’s response and offer empathy and reassurance helps to promote patient trust, improve the quality and accuracy of patient-provider communications, and increase providers’ professional satisfaction from more meaningful patient-provider relationships.

In Summary

The TRIADS Framework is designed to understand patients and families holistically by inquiring supportively about their adversities, distress, and strengths. Healthcare teams use this understanding to engage their patients in addressing medical conditions and supporting sources of strength and resilience. This support can include explicit encouragement for sound daily practices in diet, sleep, and bodily care; safety in intimate and family relationships; meaningful engagement with the community; and activities that promote wellness in the face of adversity.

Healthcare teams also have an important role to play in addressing structural and systemic racism and sexism and all forms of discrimination. They can be actively engaged in learning about and changing power structures and traumatic systemic practices in relationships with patients, within the clinic, and in the community. Through this commitment to health at the individual, family, and community levels, healthcare teams can become effective allies in confronting the forces that perpetuate the disproportionate incidence and negative impact of adversity among low- income and racial and ethnic minorities.

References

- Lieberman, A. F., Ippen, C. G., & Van Horn, P. (2006). Child-parent psychotherapy: 6-month follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 45(8), 913-918.https://doi.org/10.1097/01.chi.0000222784.03735.92

- Machtinger, E. L., Davis, K. B., Kimberg, L. S., Khanna, N., Cuca, Y. P., Dawson-Rose, C., Shumway, M., Campbell, J., Lewis-O’Connor, A., Blake, M., Blanch, A., & McCaw, B. (2019). From Treatment to Healing: Inquiry and Response to Recent and Past Trauma in Adult Health Care. Womens Health Issues, 29(2), 97-102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2018.11.003

- Pediatric Integrated Care Collaborative (PICC). (2016). Improving the Capacity of Primary Care to Serve Children and Families Experiencing Trauma and Chronic Stress. A project of the Center for Mental Health Services in Pediatric Primary Care. Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University. https://picc.jhu.edu/the-toolkit.html

- National Council for Behavioral Health (NCBH). (2019). Fostering Resilience and Recovery: A Change Package for Advancing Trauma-Informed Primary Care. The National Council for Behavioral Health.https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/fostering-resilience-and-recovery-a-change-package/

- The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. (2019). Fostering Healthy Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Development in Children and Youth: A National Agenda. Washington (DC): The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. https://doi.org/10.17226/25201

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2014). SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. Rockville, MD: SAMHSA https://ncsacw.samhsa.gov/userfiles/files/SAMHSA_Trauma.pdf

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245-258.

- Merrick MT, Ford DC, Ports KA, et al. Vital Signs: Estimated Proportion of Adult Health Problems Attributable to Adverse Childhood Experiences and Implications for Prevention – 25 States, 2015-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(44):999-1005.

- Wade R, Jr., Cronholm PF, Fein JA, et al. Household and community-level Adverse Childhood Experiences and adult health outcomes in a diverse urban population. Child Abuse Negl. 2016;52:135-145.

- Cronholm PF, Forke CM, Wade R, et al. Adverse childhood experiences: Expanding the concept of adversity. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(3):354-361.

- ACEs Aware. ACE Screening Clinical Workflows, ACEs and Toxic Stress Risk Assessment Algorithm, and ACE-Associated Health Conditions: For Pediatrics and Adults. April 2020.

- Friedman MJ. Finalizing PTSD in DSM-5: getting here from there and where to go next. J Trauma Stress. 2013;26(5):548-556.

- Masten, A. Ordinary Magic: Resilience in Development. New York: The Guilford Press, 2014.